“I am afraid all the time. Every time my dad leaves for work, I am afraid,” says a soft-spoken University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee student who is the daughter of undocumented parents who came to the United States from Mexico decades ago in search of greater opportunity, new jobs and a better life.

The reality for this student and her parents is that every day harbors uncertainty and the simple drive to work is fraught with peril. The student dreams of telling the stories of her people: The people who go unseen and who exist quietly and carefully, thinking through every movement, from cautiously driving the speed limit to watching who you befriend to never going on vacation because you can’t risk your passport being checked.

The student shares the importance of voting in her community. She is a citizen, even though her parents still are not (they work in blue-collar businesses in the Milwaukee area), and she feels simultaneously compelled to speak on behalf of all her people but too frightened to allow the printing of her name. “My voice is important because it is my parents’ voice,” she tells Media Milwaukee.

“You know,” she adds, becoming emotional and emphasizing the core point she wants people to remember:

“We are people too.”

The public controversy tends to focus on the border and migrant caravan or on Washington D.C. and Donald Trump’s desired wall and national emergency declaration. However, a team of 16 Media Milwaukee student journalists set out on a three-month investigative quest to better understand the immigration question in one major Midwestern community – Milwaukee, Wisconsin – where there is a thriving immigrant population but the topic doesn’t often make national headlines.

Wisconsin is 35th in the country when it comes to the number of ICE detainer holds, with just over 10,000 dating back to 2005. That number comes from a Syracuse University center that has obtained aggregate, comparative numerical data from ICE for years. However, ICE is ramping up secrecy, making it harder for the national clearinghouse to provide even aggregate numbers. Through dozens of open records requests with local jails and the state prison system, Media Milwaukee obtained more than 500 names of people with ICE detainers filed against them since 2014. That allowed the student journalists to get a better picture of how ICE operates in Wisconsin.

Throughout Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the United States, unauthorized immigrants silently live their lives, often economically enriching the communities in which they live, propping up industries (such as the food and dairy industry) with their backbone, holding positions in restaurants but often living in poverty themselves, enrolling in the state’s universities and technical schools, and trying to satisfy themselves as a people, while living in shadows juxtaposed against and in an immigration system almost everyone agrees is broken. When the students started the project an instructor asked if any knew an unauthorized immigrants, many hands raised.

In some cases, as with the complexity of any community, the people who came here are less sympathetic.

What the student journalists found: A system clamped down with secrecy, in which the government – and Wisconsin court system – make it almost impossible to put a human face on who is being deported or whom ICE is trying to detain, including a state Supreme Court that doesn’t want names listed in ICE detainer holds released and a federal government that legally prohibits the public from knowing whom exactly, some might argue, the government manages to systematically “disappear” from communities where they’ve sometimes lived for years. The secrecy justification dates to the 9/11 terrorist attacks but is now applied to an entirely different debate. What does flourish: Rampant fear in the community fueled by the quick-hit of social media and lack of governmental transparency.

Media Milwaukee was able to obtain hundreds of names of people with ICE detainers filed against them likely only due to confusion among local agencies over the state of Wisconsin law, which, since a 2017 state Supreme Court decision, has forbade such release to the public. Multiple state and county agencies refused to release names and even aggregate numbers of ICE detainers in Wisconsin, with some citing that court decision.

At the same time, there exists a complex web of organizations and people who try to humanize and help those who are unauthorized, from a Latino newspaper editor to immigration lawyers to an advocacy group that holds driver’s licensing events for immigrants.

“The ability to do this stuff in secret and, by that I mean, the ability to take faces away from the people detained…then they are not human beings,” says Peter Earle, a local attorney who unsuccessfully tried on behalf of an immigration rights organization to get Milwaukee County Jail ICE holds released to the public so the community could learn who the government has scooped up (Milwaukee and Dane County Jails have by far the most ICE holds issued in the state of any agency.)

Humanized portrayals in the media can lead people to formulate their own conclusions, but misinformation can offset that, keeping everyone in embryo.

“…The possibility of empathy is…removed from the political discourse because they are faceless,” Earle says. “People don’t even know how. We don’t even know how many they are. We don’t know what their names are. We don’t know what their stories are.”

Others end up in Dodge and Kenosha or funneled down to Chicago’s immigration courts, where a judge must sign off on deportation, their stories only episodically told now and then through activist press release or family media outreach. The greater majority simply go untold.

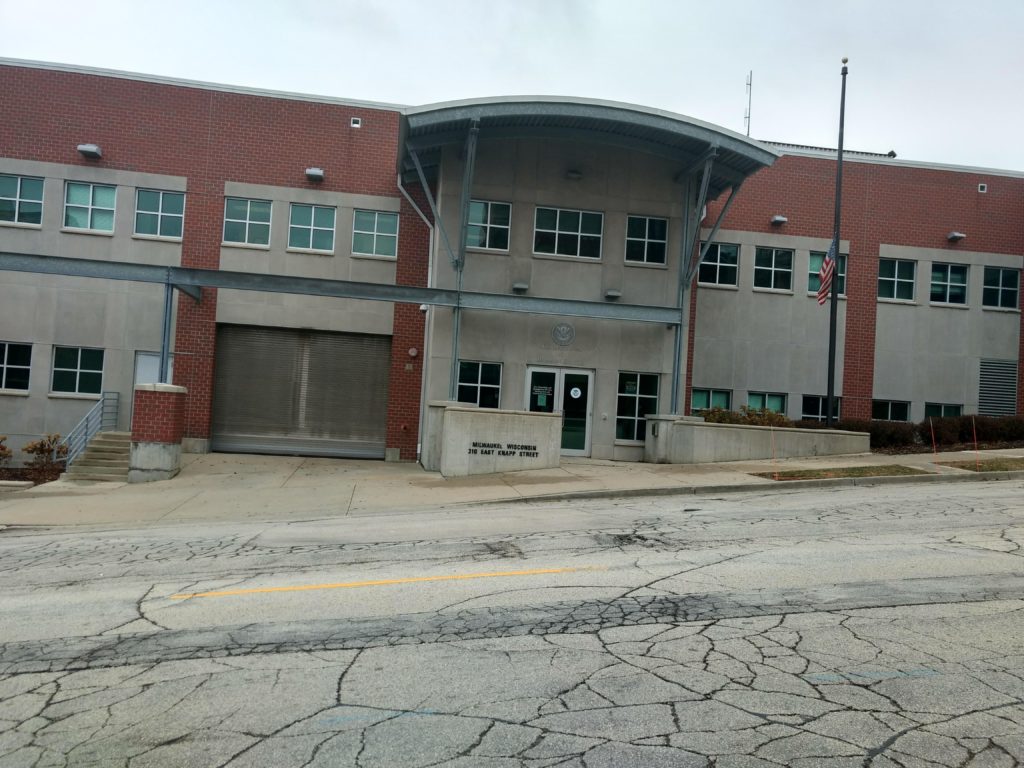

That’s truer yet when it comes to the people ICE rounds up who are not in correctional facilities. They are the “vanished,” at least to the general public. There is a Milwaukee “hold room” run by ICE, but not much is known about the people sent to it. You can’t get a list of those kept there or get a tour, although Syracuse University’s TRAC program says 682 people were detained there in the last year for which data was available, most for less than a day, 85 percent of Mexican heritage, and one-third being sent there directly as a first detention stop, with the rest transferred from another ICE facility.

“A vast majority are hard working people, who want to make a living and support their families, and have to come to think of this country as home,” said Cain Oulahan, a Milwaukee immigration lawyer. “They are giving back and are very positive people. Sure, some have criminal records – in many cases a bad mistake they made when they were younger. And in many cases have tried to turn their life around and make up for it. It is very rare that I encounter someone who has bad intentions. A vast majority are really good folks, and are only a problem because they lack status.”

The student journalists, some of whom are bilingual themselves, attended a Spanish-language driver’s license event, conducted interviews in Spanish, and attended a naturalization ceremony. They covered the Milwaukee police chief’s meeting with the Mexican consulate, an immigration panel at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and a talk by the new sheriff. They found social media aflame with claims that ICE was randomly targeting people for deportation, and they attempted to determine who the agency is focusing on and to what degree.

Student journalists interviewed sheriffs, community activists, ICE spokespeople, immigration lawyers, professors, and, most critically, the unauthorized immigrants who are marginalized to statistics, without a pulpit to humanize themselves. The students also filed dozens of open records requests with county jails and the state prison system in a quest to better understand ICE’s priorities, although studies have found that the rate of criminalization is lower in the unauthorized community than outside of it. They interviewed people on both sides of the political aisle. They also sought a list of all names of those detained from ICE – including people without criminal histories and who were not sitting in correctional facilities when they fall upon the system’s radar – but were ignored.

Among the student investigative findings:

- Although nationally, the political discourse on immigration is often dominated by politicians and the president, in Wisconsin, it’s county sheriffs who stand at the vanguard of the decisions on immigration enforcement in their communities. And they vary widely on that in a way that sometimes follows the fractures of this purple state’s polarized politics. For example, Republican-rich Waukesha County is one of only 78 jurisdictions in the entire country to join with ICE in an unique program that gives local law enforcement immigration authority (and one of just three agencies in the Midwest.) Yet, adjacent largely Democratic Milwaukee County has seesawed back and forth in how it approaches ICE detainer holds depending on the elected sheriff. A pattern of other sheriffs argued that detainers may be unconstitutional, said they won’t honor them, or said they want to see a warrant first.

- Consider, for example, the strong words of former Milwaukee County Sheriff David Clarke, long one of the state’s most vocal proponents of tougher immigration enforcement: “They’re illegal aliens in the country illegally… They’re in the country illegally. They trespassed into the United States. If you did that to Mexico or you did it to Iran or you did that to China, you would be arrested and jailed, but all of a sudden the United States wants to enforce immigration laws and they become the bad guy. This is nonsense. That’s why I’m glad that this president is pushing back and pushing back hard on this issue.” Then, consider the words of his replacement, new Sheriff Earnell Lucas, who says, “From the start of my campaign, I’ve stated that I was not going to collaborate with ICE when it relates to detaining individuals. I’m not going to drive wedges into our community for the purposes of ICE.”

- The lack of transparency in how ICE operates and who it seeks to detain leads to widespread fear in the community, often metastasizing on social media. And while ICE maintains it focuses on those who are a threat to public safety, the media and public are basically left to take their word for it. The Wisconsin Supreme Court in 2017 even overturned lower courts and ruled that federal law bars the public from knowing which people in county jails have ICE detainer holds placed on them. The question of whether the detainers must be released under open records laws before inmates are transferred to federal custody is a hotly contested one.

- Some immigration activists and lawyers say they’ve seen an increase in aggression and decline in discretion from ICE. They raise a myriad of issues, including unauthorized people who can’t afford lawyers; who have their bail confiscated or who are located by ICE at probation offices; who end up on ICE’s radar for alcohol-fueled offenses, like drunk driving or for simple marijuana possession cases; and who have American-born children but are deported anyway. “I think that the law is not family-friendly,” says Davorin Ordcic, a Milwaukee immigration lawyer. “In fact, I would say that it is anti-family. I think where the law is unfair is where there are people who have settled and developed roots here, have family members and citizen children who depend on them. There is a lot of collateral damage when a parent gets deported.” Adds Aissa Olivarez, of the Community Immigration Law Center in Madison, Wis.: “Now, we’re just seeing it be done with little discretion.”

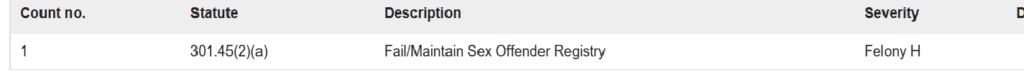

- The subset of unauthorized immigrants with ICE detainer holds who are under the supervision of the Wisconsin Department of Corrections, which includes the Wisconsin prison system, from 2014 through fall 2018, includes 18 convicted murderers. Almost 50 percent of those on the prison list are registered sex offenders, according to a response to a Media Milwaukee open records request. Media Milwaukee obtained all 275 names and ran them in the court website. In some cases, the student journalists found, the state has indicated it has lost track of registered sex offenders with ICE detainers during that time frame, even occasionally filing felony charges against such inmates for non-compliance with the Wisconsin sex offender registry. However, the overall number is a drop in the bucket compared to the overall prison population. Twenty of those people on the prison list were listed as being on active community supervision; one had absconded and one was living in Louisiana. Some of the people on the prison list had multiple previous felony convictions in Wisconsin.

- There is widespread confusion among Wisconsin sheriffs about whether the public can learn about ICE detainer requests in their jails. Media Milwaukee sent open records requests to most Wisconsin sheriffs, seeking both the aggregate numbers and actual ICE detainers. Their responses varied widely. For example, Dodge County refused to give one of our journalists any detainee information without authorization from ICE; Shawano County wanted to charge over $19,000; some counties didn’t respond at all (a violation of open records laws), and others sent over scads of names and even, in a few cases, fully filled out detainer forms.

- According to the Syracuse center’s data, Barack Obama deported a lot more people and more ICE detainers were issued nationally each year during his administration than in Donald Trump’s first year in office. According to Syracuse University’s TRAC database, the most deportations by ICE from 2012 through 2017 occurred in 2012, when there were just over 400,000. In 2017, there were 226,119 deportations, the least of any year since 2012.

- Unauthorized people living and working in the Milwaukee area describe arduous journeys to get here and, for the most part, said they came to economically support families back home. They describe a fairly fluid system in the past, in which people went back and forth between home country and here. They also describe growing fear in the age of Trump and hurt over dehumanizing rhetoric. “The most difficult part is leaving your family behind,” says Juan, an unauthorized immigrant working in a Milwaukee-area restaurant (Media Milwaukee is withholding his full name for his protection.) He gave the interview in Spanish: “Lo más dificl es dejar la familia.”

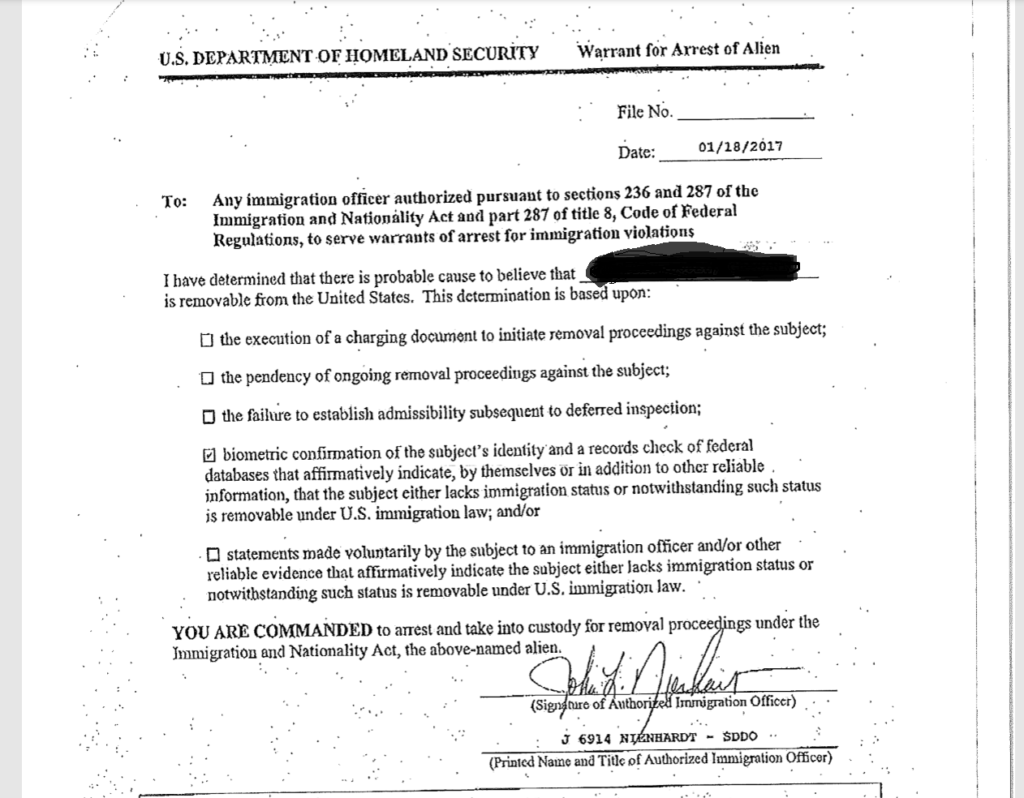

Here are examples of some of the forms the student journalists received from county-level authorities. After much debate, the students redacted names if they weren’t able to reach inmates for their side. The prison system refused requests for interviews.

Here is a Wisconsin inmate ICE detainer from a county jail.

Again, Media Milwaukee received the name but blacked it out because the students were not able to reach the inmate in question.

Raids and Fear

How is ICE finding people in Milwaukee, and where do they go from there? Media Milwaukee posed those questions to Sarai Melendez, the workers’ center organizer and receptionist for Voces De La Frontera. The group was founded as a workers’ center. Along the way, immigration became part of the worker rights’ movement and part of Voces, one of the state’s most vocally anti-ICE groups.

Melendez mentioned that there are a few ways that ICE is finding unauthorized immigrants, but one of the most common ways is if the person has multiple reentries and has been contacted by immigration in the border. If they are caught by la patrulla (people in the military), fronteriza (people who work in the border) or ICE agents, they take them in to get their fingerprints printed and that stays in the system forever. Once they reach Wisconsin, she said, some people come on the radar of law enforcement by driving without a license.

If the person is being deported, they put them on a plane that will take them to a detention center that is closer to the border, she says. Once the person arrives at the detention center, a bus takes them inside Mexico; but the bus only drives the person 20 miles inside of Mexico’s border, according to Melendez.

Then the Mexican consulate or Mexican government greet them and take them to a building where they are able to make one call and receive a small amount of money. After that is all settled, says Melendez, the unauthorized immigrant is left to find a way back home.

“At the end of the day, all these people want to do is reach that American Dream, and we are going to be there for them no matter who is in office,” said Jasmine Gonzalez, Communication Coordinator for Voces De La Frontera.

Voces has gathered some of the more sympathetic stories and publicized them, highlighting the children left behind; for example, the group tells the story of Erick Gamboa Chay, whom it says was detained by ICE in Milwaukee in 2018, leaving behind his wife and three children under age 8, including a boy who has sickle cell anemia and “requires constant care.” Voces alleges that Gamboa Chay “appears to have come to ICE’s attention after being stopped for driving without a license.” The latter is indeed the only offense that comes up for Chay on the state court website, a Media Milwaukee review shows.

In another case, Carolina Brumfield of Waukesha, Wisconsin has created a GoFundMe page called Free Franco. “Franco Ferreyra, my brother, a young father of four beautiful children, an amazing human being, with the biggest heart someone could have was detained by ICE and ripped away from his family unjustly, on Monday morning, June 11, 2018,” the site reads. The page has raised more than $6,000.

“As you can imagine our family is in a state of crisis and heart broken. In order to fight for his freedom, and to reunite him with his children and family, we have to pay for very expensive lawyer fees, immigration fees, form fees, etc. and unfortunately, we simply don’t have the sufficient funds to help him on our own,” continues the page. Media reports say Ferreyra had a past OWI and driving without a license incident, came to the U.S. at age 13, and was detained when meeting with immigration officials on the driving without a license infraction.

Media Milwaukee reached out to Brumfield, but she did not want to talk.

In contrast, the press releases whipped out by ICE on immigration raids in Wisconsin highlight criminality. For example, in September 2018, ICE announced it had rounded up 83 “criminal aliens and immigration violators” in the state, largely people of Mexican heritage who lived in communities all throughout the state. In 16 cases, the people had no criminal histories, but ICE also listed a litany of other past offenses, ranging from child abuse to larceny or reentering the U.S. after a previous deportation, which is a felony. The agency insists its raids are “targeted.”

The government’s rhetoric combined with secrecy and human stories that filter through the community add up to creating a lot of fear. Jessica Cavazos, the President and CEO of the Latino Chamber of Commerce in Dane County, described rampant fear in the community instilled by loose social media talking. She describes businesses closing and people skipping work when word of ICE raids spreads.

“We really need a pathway to legalization and citizenship that we don’t have,” says Cavazos, who reinforced her viewpoint that members of the Latino community generally strive to be a part of the U.S. economy. “The best way to say it is, right now, there is a witch hunt after the wrong people.”

Vidal is an unauthorized immigrant in Milwaukee who is seeking legal status.

“I know I am going to become something sooner or later,” Vidal told Media Milwaukee. In the cases of unauthorized immigrants interviewed or their family members, Media Milwaukee had the full names of people interviewed but decided not to print them because it could expose those interviewed to potential harm. The more important thing was to gather their perspectives. The student journalists also made requests to interview people incarcerated in the state prison system, but authorities refused those requests. The student journalists wanted to defuse simplistic rhetoric’s spot at the front of the American conversation by looking at the issue from all directions.

“If you do it with love, you are going to make it,” says Vidal, who walked for four days and three nights at the age of 17 to pursue his dream of coming to America (he recalls how some people ended up with broken legs, some didn’t make it at all, and how “we had to drink dirty water that cows drink.”) He worked on a farm, as an overnight dishwasher, and then as a busboy, living in relatives’ homes and a trailer, and still finding time to learn English at a technical college. He is now a married 29-year-old with a job and a dream to one day become an entrepreneur.

“Dream big baby!” he shares. “If an illegal immigrant is working for his dream, why can’t you?”

Growing Secrecy

It’s possible to get some aggregate numbers that shed light on ICE activities in Wisconsin.

From 2005 to April 2018, 10,696 detainer holds were placed on people in Wisconsin by ICE, which withheld information on how many of those people had criminal histories, according to Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, which is run by Syracuse University. That makes Wisconsin the 35th highest state in the country, its numbers dwarfed by border states and also less than some other areas of the Midwest, such as Minnesota and Iowa.

According to data from Syracuse University, Wisconsin was ninth among all 12 Midwestern states for the total number of ICE detainers issued from August 2005-April 2018 (10,696) and in the year 2017, Wisconsin was 25th in the country (1,180).

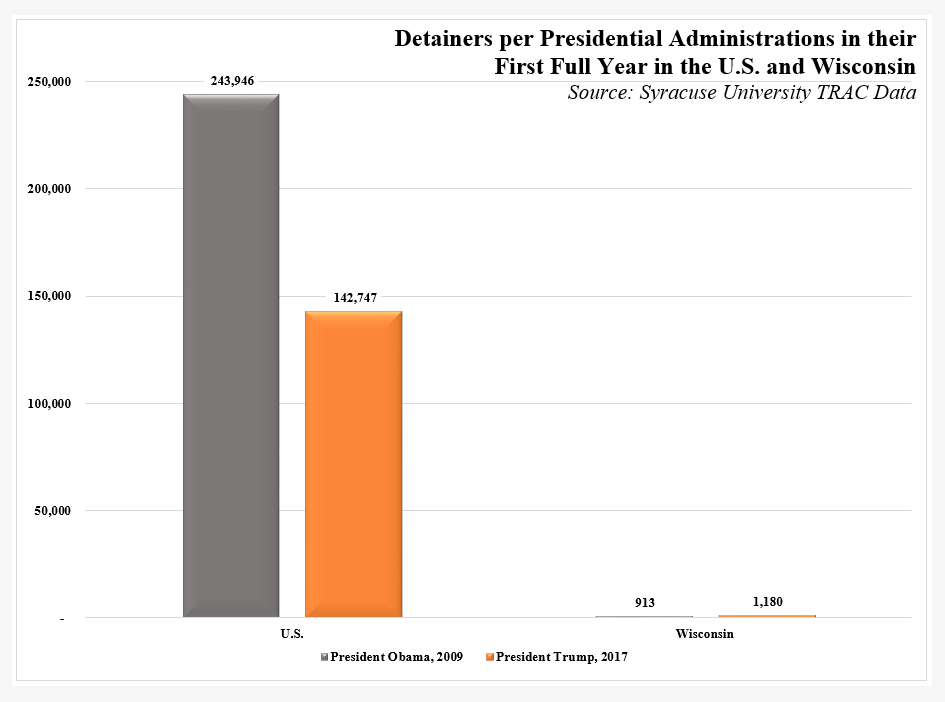

TRAC data demonstrates that nationally, there were more ICE detainers issued in President Barack Obama’s first full year in office (243,946 in 2009) than in President Donald Trump’s (142,747 in 2017). However, more ICE detainers have been issued under President Trump in Wisconsin during his first full year in office (1,180 in 2017) than in President Obama’s (913 in 2009).

On the national level, secrecy is increasing and such information may no longer be as fully available. The co-directors of TRAC, Susan B. Long and David Burnham, are currently suing ICE for violating the Freedom of Information Act and “unlawfully withholding record related to CE’s immigration enforcement actions and its interaction with other law enforcement agencies,” according to a TRAC press release

In January of 2017, ICE began refusing to provide details, such as the criminal records of people held on ICE detainers and whether those people were deported.

According to the release, ICE stated their release of information in the past was “discretionary” and they have decided not to release information to the public, which TRAC is arguing violates the Supreme Court’s ruling on FOIA’s, which is ironically listed on the Justice Department’s website:

“[The] basic purpose of FOIA is to ensure an informed citizenry, vital to the functioning of a democratic society, needed to check against corruption and to hold the governors accountable to the governed.”

In Wisconsin, the state Supreme Court, too, has brought down the curtains of secrecy, ruling that the public is not entitled to know whom ICE tries to detain in county jails. The liberal justices dissented, and the court’s conservative wing overturned appellate and lower court rulings that sided in favor of release in the case brought by Voces.

Essentially, the court argued that a federal law prohibited release. That law, which dates to a few years after the September 11, 2001 tragedy, was concerned in part about releasing detainer lists because of terrorists, saying doing so “could give a terrorist organization or other group a vital roadmap about the course and progress of an investigation” as well as protecting detainees’ privacy interests, the court wrote.

The federal law reads: “No person, including any state or local government entity or any privately operated detention facility, that houses, maintains, provides services to, or otherwise holds any detainee on behalf of the Service (whether by contract or otherwise), and no other person who by virtue of any official or contractual relationship with such person obtains information relating to any detainee, shall disclose or otherwise permit to be made public the name of, or other information relating to, such detainee.”

Despite his rhetoric about the subset of unauthorized immigrants who commit crimes, Sheriff Clarke opposed the release to the public of information about them.

In 2015, Milwaukee County Circuit Judge David Borowski issued a writ of mandamus, ordering Clarke to produce the information. The appeals court sided with Borowski in 2016. The conservative-controlled Supreme Court disagreed.

The argument on the side seeking release held that the detainer forms (called I-247 forms technically) are requests for holds (indeed requests sometimes not honored), and that the individuals are in the custody of county or state facilities and are not yet in federal custody.

There is widespread confusion among Wisconsin sheriffs about this angle – even when it comes to releasing aggregate numbers without identifying details. For example, the Kenosha County Sheriff cited the Supreme Court decision in denying Media Milwaukee’s request for the detainers in that county jail from 2014 to 2018. However, he did provide the aggregate number – 86 – and a list with some information sans names, which you can see below. The student journalists had requested both the names/actual detainers and aggregate numbers without identifying information for 2014 to October 2018.

The Dodge County Sheriff’s Department also cited the state Supreme Court case in denying the information, writing, “In order for me to attempt to fill your request, you will have to obtain authority through ICE directing this agency to release such information to you as it is related to ICE detainees. If approval is received from ICE, I will further need to redact any personally identifying information from the record.” Unlike Kenosha, though, Dodge did not provide the requested aggregate numbers.

Milwaukee County told Media Milwaukee that the year-to-date number of ICE detainers placed on people in its jail was 91 through November 2018. From 2015 to the most recent year available, Milwaukee and Dane Counties had the most detainer holds issued of any Wisconsin agency, per TRAC. (Not all detainers issued result in ICE actually taking custody of the person.) Here’s the top 10:

The months with the highest number of ICE detainers filed in Wisconsin since 2005 were January 2017 and August 2011, according to TRAC, with the 2011 figure being the highest month since 2005. The data stops in April 2018. The year 2011 is the most active month for ICE detainers in that time frame, according to the TRAC data.

The court decision aside, some departments responded quickly by email because they had so few cases. For example, Grant County emailed the name of an inmate with a detainer, adding, “Charge: 940.225(2)(cm) – 2nd Degree Sexual Assault-Intoxicated Victim.” Some counties, such as Ashland, Green, Florence, and Crawford, responded that they had none.

“We estimate that it will take 20 hours give or take to complete the manual search. We would need six to eight weeks to accomplish the search at a cost of approximately $1,000.00 give or take,” wrote the Iowa County Sheriff’s Department. Yet, others provided lists of names for free or a few dollars.

Some agencies – such as Oneida County – said they would have to create a new record or conduct an intensive and time-consuming search to determine the information, even in the case of aggregate numbers without names. The Sawyer County Sheriff said that agency has very few ICE detainers, but it would require a lot of work to come up with the number or list because it would entail going through thousands of inmate records to find them.

Indeed, multiple Sheriff’s Departments, and the Wisconsin prison system, freely provided lists of names of people with ICE detainers. St. Croix County emailed the student journalist five names but declined to release dates of birth, and also provided this information:

2014 – 2

2016 – 1

2017 – 1

2018 – to date (10/24/18) – 1

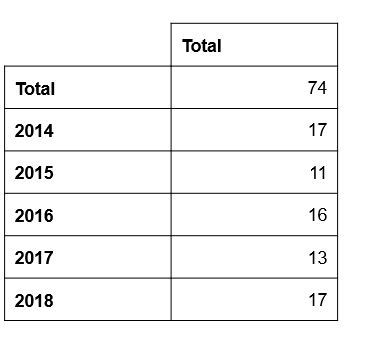

Marathon County emailed pages of names, 74, in all. One had two ICE detainers lodged on different dates. The county also provided this chart:

Names were provided to the left of the below document:

Rusk County emailed three names, two being held for alleged sexual assault and one for a warrant. LaCrosse County sent over a similar chart with 12 names but included the alleged offense, including these:

Marquette County emailed over four booking forms that included names and photos. Again, Media Milwaukee has redacted the inmates’ names only because they could not be reached for comment, in fairness to them. However, the release helped the student journalists form a picture of some of those the government wanted detained. For example, the students ran more than 200 of the jail names they received in the Wisconsin online court records system. They discovered a pattern existed in which some of those with ICE detainers did not appear to have any Wisconsin state charges issued. Others did, and they ranged greatly in seriousness from things like operating with a revoked license to homicide.

In other words, it’s easy to find examples that match the rhetoric on either side of the spectrum if one is looking for it. Perhaps the truth is far more gray and complex.

Manda Walters, an ICE spokeswoman, told Media Milwaukee that, in order for ICE to take any interest in an individual, the person’s case must be related to such things as concerns about public safety (such as those with criminal histories), terrorism, or who already have removal orders. “I can tell you in our last quarter date, from February 2018 Quarter 1 to Quarter 3, that we removed 189,000 people from just the six-state area” that includes Wisconsin, she said.

To be sure, those sitting in correctional facilities are the least sympathetic among the group, and they are not comparatively large in number. Many of those with ICE detainers in the Wisconsin prison system are convicted child molesters and some are murderers, Media Milwaukee discovered, including some felons the system says it’s lost track of. However, they are only a tiny subset of the whole even when it comes to the number of those deported. According to studies, the rate of criminalization and incarceration is lower in the undocumented population than outside of it.

“A lot of stats show undocumented immigrants are law-abiding for obvious reasons. They don’t want contact with the police,” UW-Milwaukee Latino History Professor Joseph Rodriguez said.

Immigrants, he said, “have a huge economic impact. They pay taxes, buy cars, and work decent jobs. Wisconsin is heavily dependent on immigration labor. People see immigrants as low-wage workers, but a lot of them are artists, craftsman.”

In the state prison system, ICE is focusing its resources on the most serious offenders.

The 275 people with ICE detainers from 2014-2018 in the Wisconsin prison system, which Media Milwaukee learned about through an open records request, included heroin and cocaine dealers, child abusers, burglars and more. However, they represent a microscopic percentage of the state prison population, despite rhetoric that often tries to criminalize the issue. For example, prisoners with ICE detainers in 2017 made up 0.4 percent of the state prison population.

Still, there are some bad stories to tell of those on the prison system’s ICE detainer list. For example, they include a man who killed his girlfriend’s toddler by slamming the child to the ground; a woman who cut a man’s throat; a man who broke into a woman’s house while wearing a mask and raped her; a drunk driver who killed a person pushing a car that ran out of gas; a man who alleged that three sexual assault accusers were trying to get visas to stay in the U.S. as crime victims; and a teenager who assaulted a jogger in the Northwoods.

In repeated cases, people had lengthy criminal histories, even more than 10 prior felony convictions in a few cases, and there was a pattern of people having previous probation revocations. In one case, a warrant for not being compliant with the sex offender registry was filed after the ICE detainer had been issued. It appears that, in some cases, felony charges are filed in Wisconsin by state prosecutors for sex offenders not being compliant with their registration requirements, when they were simply already deported. The degree to which they are tracked or the public is alerted in their home country is unclear.

For example, here is the court entry for one such case. “Warrant requested by the State, have information he may have been deported,” the state court entry says.

The defendant in question has a felony conviction for attempted sexual assault with use of force and, before that, a forfeiture in Wisconsin for disorderly conduct, for which he received a public defender, needed a Spanish interpreter in court, and didn’t pay his fines. ICE put a detainer on him in 2014, according to state prison records released to Media Milwaukee. In August 2014, he was sentenced to a four-year Wisconsin prison term for the felony. The felony sex offender registry violation was filed in Pepin County in October 2018.

Some immigration lawyers and activists told Media Milwaukee that ICE is more aggressive than in the past and that people can’t afford to hire lawyers or post bond and then are detained, losing the money. “We know there are good people (working for ICE), but we have seen a turn,” said Darryl Morin, past national vice president for the Midwest region for the League of Latin American United citizens.

“We have seen a pivot in the manner in which ICE operates and how far they will go, which has turned into an attack on human dignity. We’ve seen individuals picked up in front of their children. And the majority of the times we see these raids, there are no support systems put in place for the children who will be left behind. Imagine a child getting off a busy, expecting to be greeted by a parent and there is no parent?”

A National Experiment

The student journalists discovered that Wisconsin, a state whose southernmost point is nearly 1,500 miles from the Mexican border, has an anatomy few Midwestern states have, mainly because of Waukesha County’s recent inclusion in ICE’s 287(g) agreement. The only other Midwestern states with an agency signed up for 287g are Ohio and Nebraska. Texas leads the way with 287g agreements.

Just west of Milwaukee County, in one of the most Republican counties in the country, Sheriff Eric Severson’s disposition pivots sharply from his other law enforcement counterparts in Wisconsin. The Waukesha County Sheriff is a proponent of 287g, which, according to the ICE website, allows a state or local law enforcement entity to enter into a partnership with ICE, under a joint Memorandum of Agreement (MOA), in order to receive delegated authority for immigration enforcement within their jurisdictions. Severson said he wanted this authority in part to protect himself and his constituents from litigation at the hands of pro-immigration groups. A pair of correctional officers, under the instruction of Severson, were sent to ICE training. Under the federal code, this training deputizes local law enforcement to become ICE agents.

What it practically means is that anyone who lands in the Waukesha County Jail – even for the least serious offense that can get you there – will be on the radar of ICE.

You can listen to Severson discuss the issue here:

Severson insists that his county’s residents are happy with 287g, although he said that most of those who support it aren’t vocal about it. He considers the program and his intentions purposely misunderstood often from people outside of it.

“It prevents me, I think, from facing unnecessary litigation because I think we would win that, and I think people who would look at this would recognize that you can’t say I don’t have the jurisdiction to enforce ICE detainers when the very people who are doing it are federal agents.”

Still, for all the controversy and protests the program has generated, the numbers are small, according to Severson.

“On any given day, I may have only one or two people in custody that have a detainer request,” said Severson.

“Not a large number of people.”

Officers who participate in 287(g) must be a U.S. citizen, pass a thorough background investigation, have a wealth of experience in his or her current position, and have no pending disciplinary action. The program permits those designated officers to perform immigration law enforcement functions, provided that they receive appropriate training under the supervision of ICE officers.

Waukesha County signed its Memorandum of Agreement in February of 2018. Two correctional officers have completed the Designated Immigration Officer (DIO) training, whose authority remains solely within the confines of the detention center.

Severson says he has been cooperating with the Feds for decades, honoring ICE detainers prior to the implementation of 287(g) last year.

The program was an opportunity to allow compliance with the detainers, as well as the gift of jurisdiction. Severson wanted to ensure what he was doing – protecting the people of Waukesha County – was constitutional.

All 78 agreements operate under the “jail model” of 287(g), one of three models that ICE can utilize, which means that people are only screened upon arrest for criminal charges by local law enforcement.

Severson explained that if someone is arrested and found to be undocumented, having crossed the border into the U.S is a civil offense. If they are arrested, undocumented, and found to have re-entered the U.S. after prior deportation(s), then it becomes a criminal offense.

He continued on to ensure that the deputized officers do not enforce on the streets, however, if the person in question is reluctant to produce ID, they may ask some questions and let ICE know, but they do not have the authority to place that person under arrest.

The complex program, with all its intricacies, is quite hard to understand. Severson thinks that may be a reason why other sheriffs are reluctant to participate. He concluded in stating that 287(g) solves the problems that we’re seeing, and that to advance the narrative surrounding these issues, the truth has to be told.

Outspoken Trump supporter and former Milwaukee County Sheriff David Clarke echoes Severson’s opinions. Back in March of 2017, during his time as Sheriff, Clarke signed a letter of intent to participate in the 287(g) program.

“It’s a violation of our sovereignty,” Clarke says. “They trespass into somebody’s country and try to set up residency.” You can read a Sheriff Clarke-era Milwaukee County Sheriff Department press release here:

Clarke resigned in November of 2017, perhaps with the expectation of appointment to Assistant Secretary in the Office of Partnerships and Programs at Homeland Security, which never actually materialized. His successor, Richard Schmidt, was not as proactive in regards to 287(g) and the request was denied. Schmidt was then ousted by former Milwaukee Police officer and MLB security agent Earnell Lucas.

This year, Sheriff-elect Lucas intends to reverse some of the conservative views on immigration.

“A request from ICE is no different than a request from anyone in this room.” Lucas said. “This request is not to be ordered from a judge and therefore… I’m mindful of the fact that… we could be violating their constitutional right.”

Lucas promises that officers will not actively search for unauthorized immigrants; therefore, in the community they will not be associating with ICE. However, it should be noted that ICE does have their task force with agents that do go into the community when presented with a credible tip. Media Milwaukee obtained a list of ICE agents and called one of them, but was shifted to ICE PR.

At a Town Hall meeting on the South Side, in front of a crowd of Spanish speaking members of the community, Milwaukee Police Chief Alfonso Morales echoes Lucas’s statements, saying that police press immigration status when suspects are involved in serious crimes, like armed robbery, nonfatal shooting, homicide, and drug related arrests.

The Mexican Consulate in Milwaukee says that victims of domestic violence or theft, among other crimes, are reluctant to contact police out of fear that they might question immigration status.

“Milwaukee is not a sanctuary city,” Morales said. “We are here to enforce the laws. However, when we want to gain the public trust, we want the public to know that when they are the victims of crimes, witnesses of crimes, that they should not fear the police.”

Similarly, Dane County Sheriff Dave Mahoney says that Madison is not a sanctuary city either.

He insists that the process of immigration enforcement needs to be more clearly explained to communities that could be subject to an entity like ICE, as lack of or false information has heightened fear in those communities.

Mahoney has been enticed by ICE to apply to the 287g program, but he has refused on every occasion, saying that he has no interest, nor does he anticipate having any interest in the future. Every year, 30 to 40 individuals in Dane County have ICE holds placed on them, but none are honored, unless it is a unique situation in which a warrant is issued by a judge.

“Over three-quarters of the federal courts have determined that ICE holds are not legal,” Mahoney said. “They violated the Fourth and Sixteenth Amendments of the Constitution, specifically search and seizure, and due process.”

Human Voices

While the current administration’s stance on immigration can be reduced to a wall as the government continues its abeyance over whether the administration can secure adequate funding for the $5 billion project, which would be erected on the United States’ southern border, people like Juan, a Milwaukeean who hails from León, Guanajuato, Mexico, are taking precautions, philosophizing as a chessmaster does – three steps in advance, at least.

Juan, who has emigrated to the States on two separate occasions, was originally drawn here in 2003, as an 18-year-old, to secure a property large enough to house his parents and his siblings. There were eight of them, coming from León – the fourth most populous municipality in Mexico and a bedrock for the leather industry in the country – as he, enervated by 16-hour days and separated from his bed until well beyond the witching hour, sought better pay and fewer hours. Juan admitted the hardest part about venturing to the United States was leaving his family behind, the first time it was his parents and the second his wife and children.

In 2003 Juan was 18 years old, working, what Americans might consider ungodly long shifts, at a wholesale market in Leon, Guanajuato. With dreams to provide for his parents, brothers and sisters, he decided to embark on his first journey across the border. Juan was young, and he was scared.

After four years making progress in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, Juan was caught without a license by the police and found himself back in Mexico.

Back home, after Juan got married, he spoke to his wife about going to the United States to work again. In the beginning she was opposed, but he asked that she give him a chance. Later, he wondered if she would like to go across the border as well. It peaked her interest as first, but now she fears that if they join Juan in America she might prefer living here, not wanting to return to Mexico. So she said no, and Juan left alone again.

Coyote, or “Coyotaje” in Mexican-Spanish, is the term used in reference to the illegal smugglers that bring Mexicans to America, for a price. The Mexican Migration Project reports that immigrants who enter the United States via the southern border pay several thousand dollars in coyote fees. The trek is very dangerous, traveling through mountains and across the desert, possibly coming into contact with deadly insects, reptiles and other wild animals. Many attempt with a heart full of hope, only to be defeated along the way.

Temperatures in central Mexico during the summertime can reach peak temperatures of over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and Juan braved the worst of it on his second trip to the States almost two years ago. He traveled with his cousin a few others, walking sixteen to seventeen hours each day. At one point, Juan felt defeated, instructing his cousin to leave him, that he couldn’t do it anymore.

“There were two or four people who were severely dehydrated, and I was one of them,” Juan said.

That trip will have been his last, Juan says. Working in the United States, as a restaurant worker, has allowed him to purchase a home for himself and his parents, as well as provide for his wife and two boys back in Leon.

Juan’s story is not unique; waves of hundreds of thousands of immigrants have similar tales, bringing with them the shifting tides of triumph and defeat.

The student at the beginning of this story tries to describe her parents in a way that will humanize but not expose them.

“My parents appreciate the finer things in life,” she says. “They work hard for their money and they are proud when they get to do nice things and have nice things.”

She smiled as she thought of her mother, saying her hugs always smelled of Chanel No. 5, the perfume her mother always wears. She gave a nod to father who is a quiet man, with a small social circle, saying, “We have each other and that is enough, if my parents went back to Mexico, they would have no one else.”

For this bright student, making a difference comes in being vocal, sharing the humanity of her parents, who give to others, their community and have armed her with an opportunity to be well educated and go far in life. While people have often given her online profiles a hard time, biting back with criticism and lack of understanding, she knows her experience is similar to many others, and she wants people to recognize the humanity, and patriotism of the people in her household, who are proud of their community and, in their eyes, to be American.

New Citizens

At Cardinal Stritch University in Milwaukee, in Bonaventure Hall Sr. Camille Kliebhan Conference Center, a naturalization ceremony began. The room was packed, and people filled the seats and lined the walls. Children played on iPads. Toddlers squirmed in the arms of their parents, pining to run and play with other kids. Dozens of cell phones floated above the crowd, capturing photos of the very special moment that over 150 people, from approximately 55 different countries, had waited and worked for.

To become a naturalized citizen, an applicant must be 18-years-old and of good moral character. They must have the ability to speak, read and write English, as well as understand U.S. government and history. In regards to residence, an applicant must be a lawful permanent green card holder having lived in the U.S. for at least five years, being physically present for at least 30 months. Finally, applicants must be willing to take the Oath of Allegiance.

The judge named off countries one by one, “Albany.” Hands shot up. “Belize.” More hands raised. One after the other, hands held high. “Mexico.” Dozens of hands went up in unison, and cheers rang out – the only country to receive such applause. A single man from Spain cheered as his country was called. The atmosphere was electric, people beaming ear to ear, chatting with families, and taking pictures with their certificates in front of an American flag.

“The path to this day wasn’t easy,” said Judge Beth Hanan, presiding in Milwaukee and Green Bay. “Each of you is a person with good moral character.”

The Oath of Allegiance has two parts, which the judge carefully explained before everyone took it, reminding them that Americans are enriched be the fact that they have chosen to become fellow U.S. citizens. The Oath orders them to renounce any allegiance to any “Prince state of sovereignty” and swear all allegiance to the United States, although they are encouraged to remember and embrace their native heritage.

“The allegiance you held from the country from which you came will be destroyed, as if it never existed,” says the judge.

They stood up as applicants, right hands raised with fingers pointing to the ceiling, and sat down as citizens. One young girl wore a red shirt “DEPORT RACISTS,” stitched across the front.

Another teenager turned to look at her mother. “Mom, now we are equals,” she said, holding her in a long embrace.